A collaboration between Henrik Knarborg and Marion Reuter, The Danish National School of Performing Arts.

Aim

To explore and enhance musical interpretation through a theatrical approach that integrates staging and text.

Work

Iannis Xenakis’ Psappha with selected fragments of Sappho’s poems (in Danish by Mette Moestrup), performed by Henrik Knarborg.

Psappha & Sappho

Xenakis wrote Psappha in 1977 using a radical novel notation that leaves many aspects of the work open to interpretation, including the choice of instruments and the relation between each impulse. The title references Sappho, a pioneer in ancient poetry known for her stanzas of four lines with specific syllable patterns and metrical constraints. Unfortunately, only short fragments of Sappho’s poetry have survived, leaving much of her work unknown. This enigmatic nature is mirrored in Psappha, which leaves many important choices to the performer and includes large gaps of silence in the music.

In our interpretation experiment, Sappho’s poetry fills many of these gaps in the music.

Two Challenges

The workshop faced two primary challenges: implementing the text meaningfully and performing it, especially given Psappha’s virtuosic nature.

Observations and Reflections from the Workshop

1. Balancing Expression Between Text and Music

Create equal expressions in text and music.

Find strategies for logical interaction (action-reaction) between text and music, while also identifying how they may simply mirror each other.

2. Interplay of Performance and Persona

Understand how to operate the body as a virtuoso musician and speaker—is it two different personas?

Recognize that the movements of musicians add a third layer to the existing music and text layer.

3. Engagement with the Audience and Textual Interpretation

Allow the musician to react to what is said, not just play.

Say the words as if you don’t understand them, leaving room for wonder.

Make the familiar unfamiliar—awaken to the ‘unknown’ by breaking conventions, as in Brecht’s Distancing Effect.”

4. Theoretical and Methodological Foundations

Don’t identify with the theater; seek to create information instead ( Barnett 2014).

Work with the “viewpoint” method (Bogart & Landau 2005).

Work with Marion Reuter’s The Carousel Method

Three Reflections on the Workshop

Is it permissible to add text?

In many concert situations, explanatory notes provide context. However, this project merges the surrounding context with the actual work, enriching the experience. Unlike program notes that explain contextualization, we create a dramatic contextualization by combining the two artworks. Since both works are in sound, they interfere and meld into a new work, especially for those unfamiliar with Psappha.

The interpreter as co-creator

Traditionally, classical musicians act as neutral ambassadors of the work. Here, the musician steps into the realm of composition, shaping the performance by determining the interaction between music and text, making it deeply personal and innovative. This brings new responsibilities, not only to the composer and author but also towards the audience. To what extent should they be informed?

Marion Reuter on the Collaboration with Henrik Knarborg

“For me, it is about creating something together that transcends our disciplines and finds its own language. Our collaboration is a celebration of the moment, involving the space, situation, and music. It’s about listening and allowing oneself to be touched by the music, triggering an impulse to think together. We create a vulnerable rehearsal space for associative thought development. Our goal is to create a scenic translation of the text through rhythmic structures and verse forms, evoking a speech act that makes the ancient text’s cultic character musically and sensually comprehensible, rhythmically and dynamically connected with Xenakis’ composition. We explored a form of speech act conditioned by Xenakis’ compositional elements and Sappho’s metrics, despite it initially feeling artificial.”

The Poems

Sappho’s work is considered pioneering not just because she invented a new verse form, but also because she explored personal and emotional themes in a way that was groundbreaking for her time. Her poetry delves deeply into love, passion, and the human experience, often from a woman’s perspective, which was relatively rare in ancient literature. This play with verse likely inspired Xenakis’s composition. Here is a brief overview of the verse.

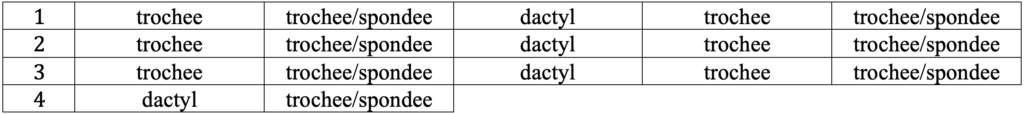

Sapphic verse uses stanzas of four lines, using the metrical feet of trochee (heavy, light), spondee (heavy, heavy) and dactyl (heavy, light, light):

Sappho’s innovation was in how she used these patterns, allowing for varied accentuation (heavy or light syllables) within the fixed structure. This broke away from the strict accentuation rules of earlier poetry, making her work more expressive and flexible. In Ancient Greek, heavy and light syllables are determined by their length (long vs. short), unlike in modern languages where stress (stressed vs. unstressed) is the key factor. Both long/short syllables and stress/unstress patterns can be found in Xenakis Psappha.

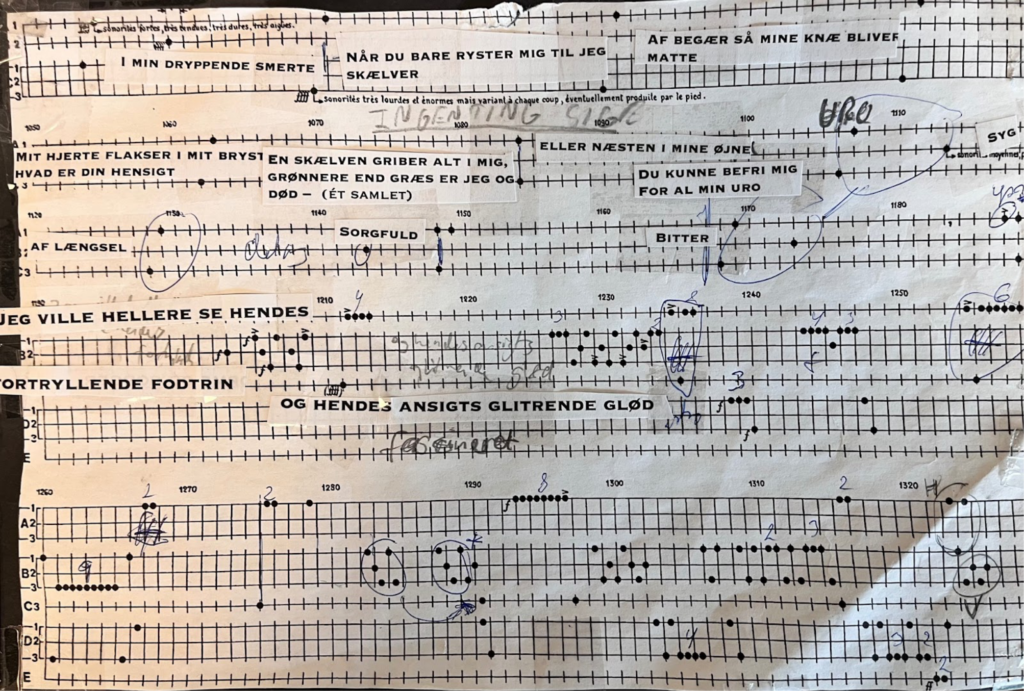

In my dripping pain, when you just shake me till I tremble with lust so my knees go numb,

my heart flutters in my chest, what is your intention

a tremor seizes everything in me, greener than grass I am and death—or almost in my eyes

You could set me free from all my anxiety, sick with longing, sorrowful, bitter, painstaking

I would rather see her enchanting footsteps and the glittering glow of her face.